|

FOCUSR [1,2] is novel algorithm for dense vertex correspondence between two surface meshes. It benefits from the speed of direct matching of features over a surface and uses spectral correspondence as a mean of regularization. Spectral methods have been used for shape matching by comparing the lowest-frequency (smooth) eigenvectors of a graph Laplacian (representing inherent geometric properties of the mesh surfaces, see Fig. 1). FOCUSR takes advantage of the smoothness of these lowest-frequency eigenvectors to regularize an embedding containing any set of extra features (e.g., metrics derived from the mesh, or external measures).

|

Eigenvectors of the graph Laplacian of a mesh represent inherent geometric properties of this surface. For ![]() vertices, let

vertices, let ![]() be the weighted adjacency matrix describing the connections between the vertices. Given a distance metric

be the weighted adjacency matrix describing the connections between the vertices. Given a distance metric

![]() between points

between points ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

The distance metric can be based on the distance between vertices:

![]() , or if additional features

, or if additional features

![]() are used (e.g., surface curvatures, mesh texture, virtually any extra measurements):

are used (e.g., surface curvatures, mesh texture, virtually any extra measurements):

where

![]() is the concatenation of the 3D coordinate values

is the concatenation of the 3D coordinate values

![]() with the

with the ![]() feature values

feature values

![]() , while

, while ![]() is a weighting parameter for each feature.

is a weighting parameter for each feature.

The general Laplacian operator is formulated as the

![]() matrix with the form:

matrix with the form:

| (3) |

where ![]() is the degree matrix (diagonal matrix with

is the degree matrix (diagonal matrix with

![]() ), and

), and ![]() is the diagonal matrix of node weights. Typically in spectral correspondence

is the diagonal matrix of node weights. Typically in spectral correspondence ![]() is set to identity

is set to identity

![]() , or to

, or to

![]() . However, it is proposed to set

. However, it is proposed to set ![]() as any meaningful node weighting (e.g., positive feature magnitudes):

as any meaningful node weighting (e.g., positive feature magnitudes):

where ![]() is the node degree (i.e.,

is the node degree (i.e., ![]() ),

), ![]() is the previously mentioned feature weights, and

is the previously mentioned feature weights, and

![]() is a function that enforces positive values (e.g.,

is a function that enforces positive values (e.g.,

![]() or

or

![]() ). The denominator in Eq. (5) contains the sum of the influences of each feature on vertex

). The denominator in Eq. (5) contains the sum of the influences of each feature on vertex ![]() . We used

. We used

![]() to promote correspondence between nodes having the largest feature components (which we assume indicate greatest significance).

to promote correspondence between nodes having the largest feature components (which we assume indicate greatest significance).

The right eigenvectors of the Laplacian matrix ![]() comprise the graph spectrum

comprise the graph spectrum

![]()

![]()

![]()

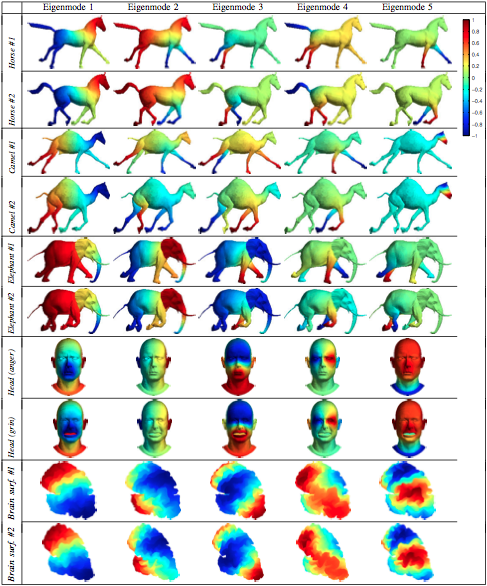

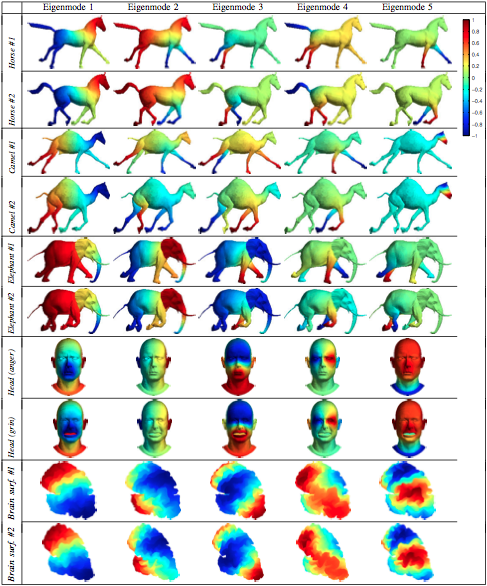

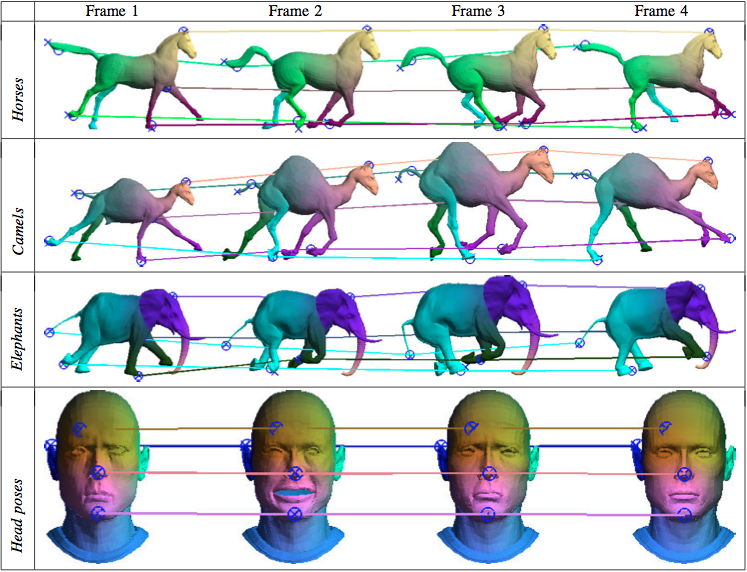

![]() . The values over surfaces for the five lowest frequency eigenvectors are shown on Fig. 1, and illustrates the stability of these eigenvectors between articulated or highly deformable shapes. here,

. The values over surfaces for the five lowest frequency eigenvectors are shown on Fig. 1, and illustrates the stability of these eigenvectors between articulated or highly deformable shapes. here,

![]() represents the 3D coordinate in space (i.e.,

represents the 3D coordinate in space (i.e., ![]() ), and the superscripted

), and the superscripted

![]() represents the

represents the

![]() th

spectral coordinate (i.e., the

th

spectral coordinate (i.e., the

![]() th

eigenvector of the graph Laplacian. Each eigenvector

th

eigenvector of the graph Laplacian. Each eigenvector

![]() is a column matrix with

is a column matrix with ![]() values, and represents a different (weighted) harmonic on a mesh surface that corresponds to an inherent property of the mesh geometry. The

values, and represents a different (weighted) harmonic on a mesh surface that corresponds to an inherent property of the mesh geometry. The ![]() values

values

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() give the spectral coordinates of node

give the spectral coordinates of node ![]() (i.e., a coordinate in a spectral domain).

(i.e., a coordinate in a spectral domain).

The first eigenvector

![]() is the trivial (uniform) eigenvector, and the eigenvectors associated with the lower non-zero eigenvalues (e.g.,

is the trivial (uniform) eigenvector, and the eigenvectors associated with the lower non-zero eigenvalues (e.g.,

![]() ) represent coarse (i.e., low-frequency) intrinsic geometric properties of the shape. The first of them

) represent coarse (i.e., low-frequency) intrinsic geometric properties of the shape. The first of them

![]() is called the Fiedler vector, while eigenvectors associated with higher eigenvalues (e.g.,

is called the Fiedler vector, while eigenvectors associated with higher eigenvalues (e.g.,

![]() ) represent fine (high-frequency) geometric properties. For example, in Fig. 1, the values of

) represent fine (high-frequency) geometric properties. For example, in Fig. 1, the values of

![]() increase along a virtual centerline depicting the global shape of the models (a coarse intrinsic property), while the values of

increase along a virtual centerline depicting the global shape of the models (a coarse intrinsic property), while the values of

![]() depict finer details of the models.

depict finer details of the models.

Only the first ![]() lowest-frequency eigenvectors (

lowest-frequency eigenvectors (

![]() and

and

![]() ) are of interest. In practice, these eigenvectors on both meshes needs to be reordered (their sign might be flipped, and due to algebraic multiplicity, eigenvectors of close eigenvalues might be swapped). Reordering is done by checking the values of these eigenvectors between pairs of closest points on the mesh surface (

) are of interest. In practice, these eigenvectors on both meshes needs to be reordered (their sign might be flipped, and due to algebraic multiplicity, eigenvectors of close eigenvalues might be swapped). Reordering is done by checking the values of these eigenvectors between pairs of closest points on the mesh surface (

![]() on mesh

on mesh ![]() is the closest point of

is the closest point of ![]() on mesh

on mesh ![]() ). The matrix

). The matrix ![]() gathers all dissimilarities between eigenvector

gathers all dissimilarities between eigenvector ![]() and

and ![]() :

:

|

The Hungarian algorithm can find the optimal permutation ![]() so each eigenvector

so each eigenvector ![]() corresponds with

corresponds with

![]() .

.

Initial feature vectors ![]() and

and ![]() are extended with the reordered eigenvectors

are extended with the reordered eigenvectors

![]() and

and

![]() to form an extended spectral embedding:

to form an extended spectral embedding:

where ![]() are weighting parameters based on the eigenvector frequencies and their reordering confidence, and

are weighting parameters based on the eigenvector frequencies and their reordering confidence, and ![]() a weghting parameter for each feature (e.g.,

a weghting parameter for each feature (e.g.,

![]() of Eq. (2) ).

of Eq. (2) ).

These spectral embeddings are regularized using a non rigid point set correspondence. Coherent Point Drift (CPD) is used [1].

The extended spectral embeddings have been regularized with the smoothness of their spectral components. Closest points between these aligned embeddings reveal corresponding points between both meshes. The correspondence map can be further regularized in space in order to respect the spatial neighborhood of the meshes. The final correspondence map is given such that:

| (8) |

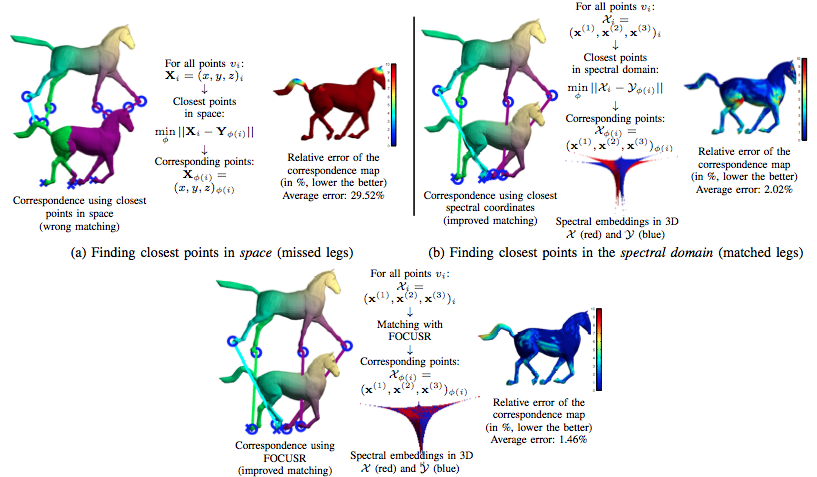

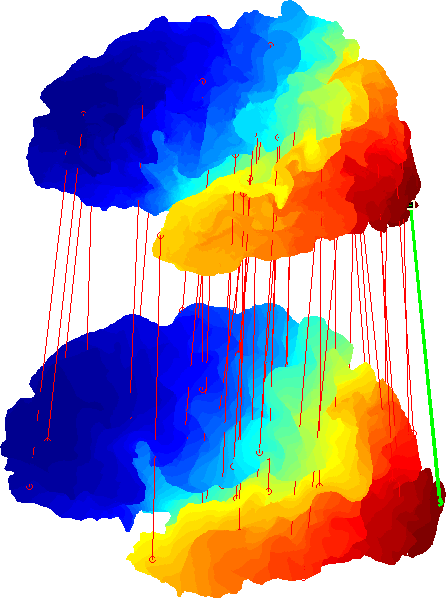

FOCUSR works on regular meshes when using its simplest setting (no additional features are required). Below, the illustration shows that finding closest points in space faces the challenge of working directly in the spatial domain, while the correspondences become clearer in the spectral domain. FOCUSR uses a different approach as it takes advantage of the smoothness of the lowest harmonics to regularize matching.

|

FOCUSR can match meshes undergoing important non rigid transformations and articulated meshes. Below are examples of galloping animals and of different facial expressions.

|

FOCUSR can also be used for precise and accurate correspondence in medical imaging. Below is a matching between two cerebral cortices which are highly convoluted surfaces. FOCUSR matches the accuracy of state-of-the-art brain matching algorithm with the benefit of being inherently extremely fast.

|

CODE IS UNDER REVISION AND AVAILABLE IN ITS CURRENT FORM FOR REVIEW ONLY

http://step.polymtl.ca/~rv101/spectral-correspondence.zip